The reason why the division of Bengal remains an understudied part of Partition is because, unlike Punjab, the partition saga in Bengal had begun before 1947 and continued till 1971

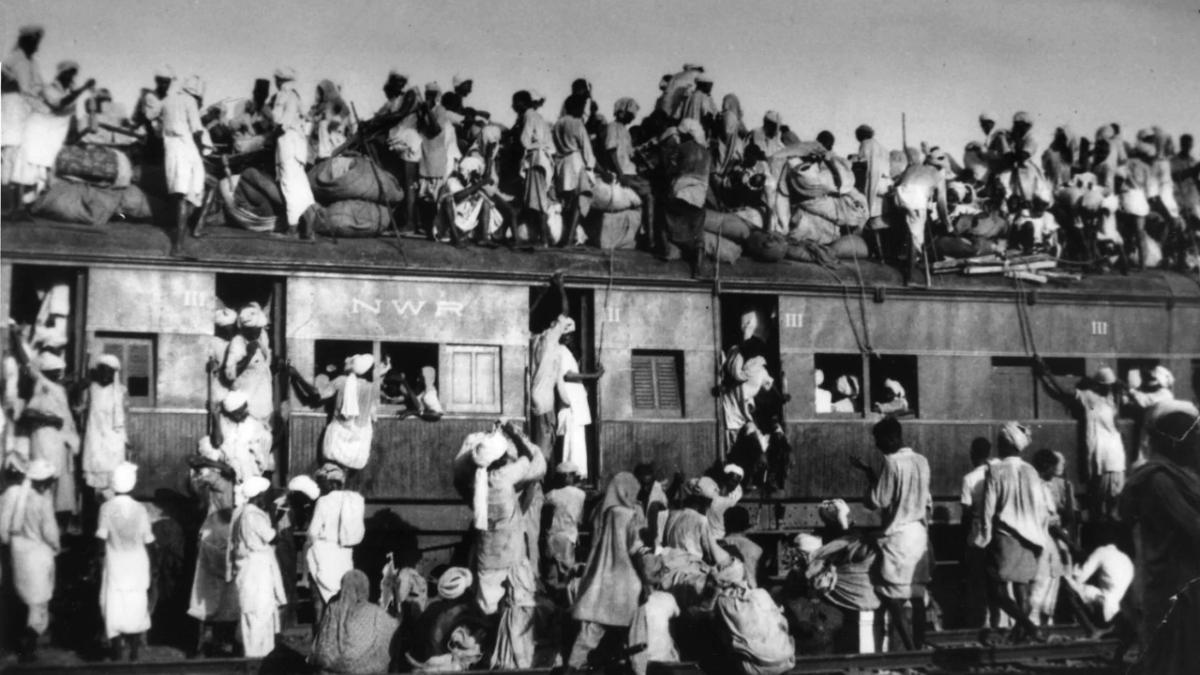

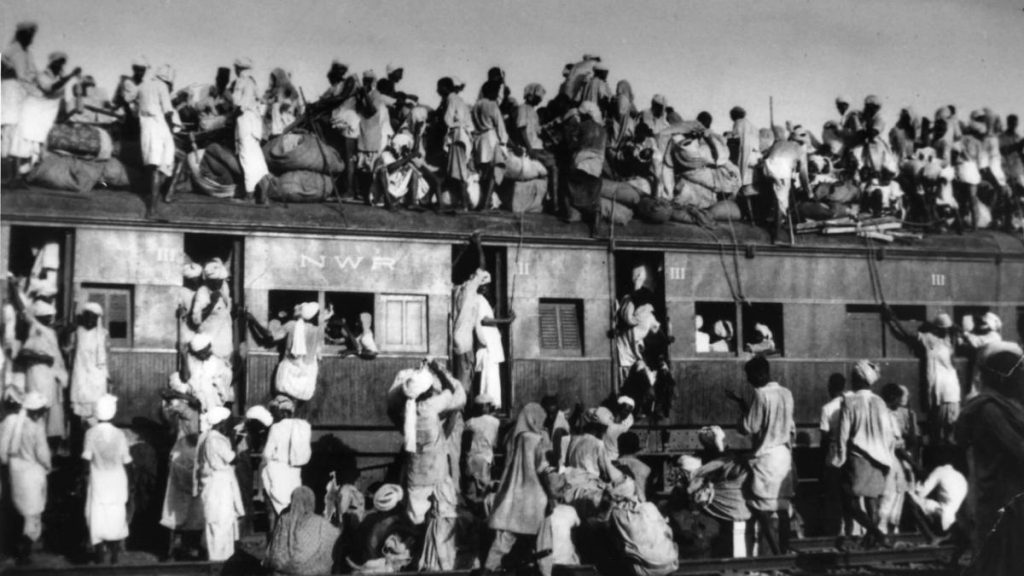

Much has been written about India’s Independence and Partition, covering the human aspects and the politics behind it. The human narrative around Partition has been shaped by fiction like Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas and Saadat Hasan Manto’s short stories, as also by films like M.S. Sathyu’s Garam Hava, Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi and Sabiha Sumar’s Khamosh Pani. All these focus on the partition of Punjab, the human tragedies of millions of refugees moving out of newly created boundaries and the senseless violence and killings that gripped both India and Pakistan. Often ignored is that the partition also divided Bengal into West Bengal and East Pakistan. Bhaswati Mukherjee’s Bengal and its Partition: An Untold Story (Rupa Publications, Rs 595) is an empathetic look into the unique political dynamics in Bengal where Muslims enjoyed a slight majority.

Perhaps the reason that Bengal’s division has remained an understudied part of Partition is because, unlike Punjab, the partition saga in Bengal had begun before 1947 and continued till 1971 when the growing alienation of the Bengali East Pakistanis and the Pakistan army’s brutal crackdown led to the emergence of Bangladesh. On its western border, India’s relations with Pakistan have remained locked in hostility; in the east, relations with Bangladesh developed their own dynamics leading to a close and sometimes difficult, but never adversarial or hostile, relationship.

Mukherjee squarely blames the British rulers for systematically eroding the syncretic culture of Bengal by inserting the communal virus into the body politic. The first partition of Bengal in 1905 along communal lines was reversed in 1911, largely on account of opposition by both the Hindu and Muslim elites, though it also sowed the seeds of the 1947 rupture. Perhaps there is an element of nostalgia in Mukherjee’s evocation of the syncretic culture, no different from what Punjabis from Amritsar feel when they visit Lahore to eat kababs and listen to Sufi qawwalis. However, the author’s Bengali passion is balanced by the historical rigour with which she approaches the subject.

Comparisons between Hindu nationalism and Muslim nationalism are a more sensitive issue. Was the latter more communal than the former? Is that what made Partition inevitable? It is difficult to find a single root cause. The communal fault-line obviously existed for the colonial powers to exploit it and the direction in which Pakistan evolved under Bhutto and Zia has taken Pakistan’s Islam further away from its subcontinental character. Lacking a shared language and culture in 1947, Pakistan sought to fashion its identity in a religion. Bangladesh has tried to define its identity both in terms of Islam and Bengaliness.

Mukherjee holds the Indian leadership responsible for ignoring the wishes of the (Bengali) people and accepting the inevitability of partition. There may be a grain of truth in this, but it is difficult to reconcile it with the growing search for identity nationalism that had gripped the world after World War I. It is a search that still continues, including in India. If seen together with the feudal nature of the landholding elites in pre-1947 India and the fact that the bhadralok that had opposed the 1905 partition found Partition more acceptable in 1947, a more complex picture emerges.

What Mukherjee’s book does is to shine much-needed light into the untold story of Bengal’s two partitions. The next step is for historians, fiction writers and filmmakers in both India and Bangladesh to collaborate and add to the narrative of the 300 million Bengalis living in both countries.